Summary

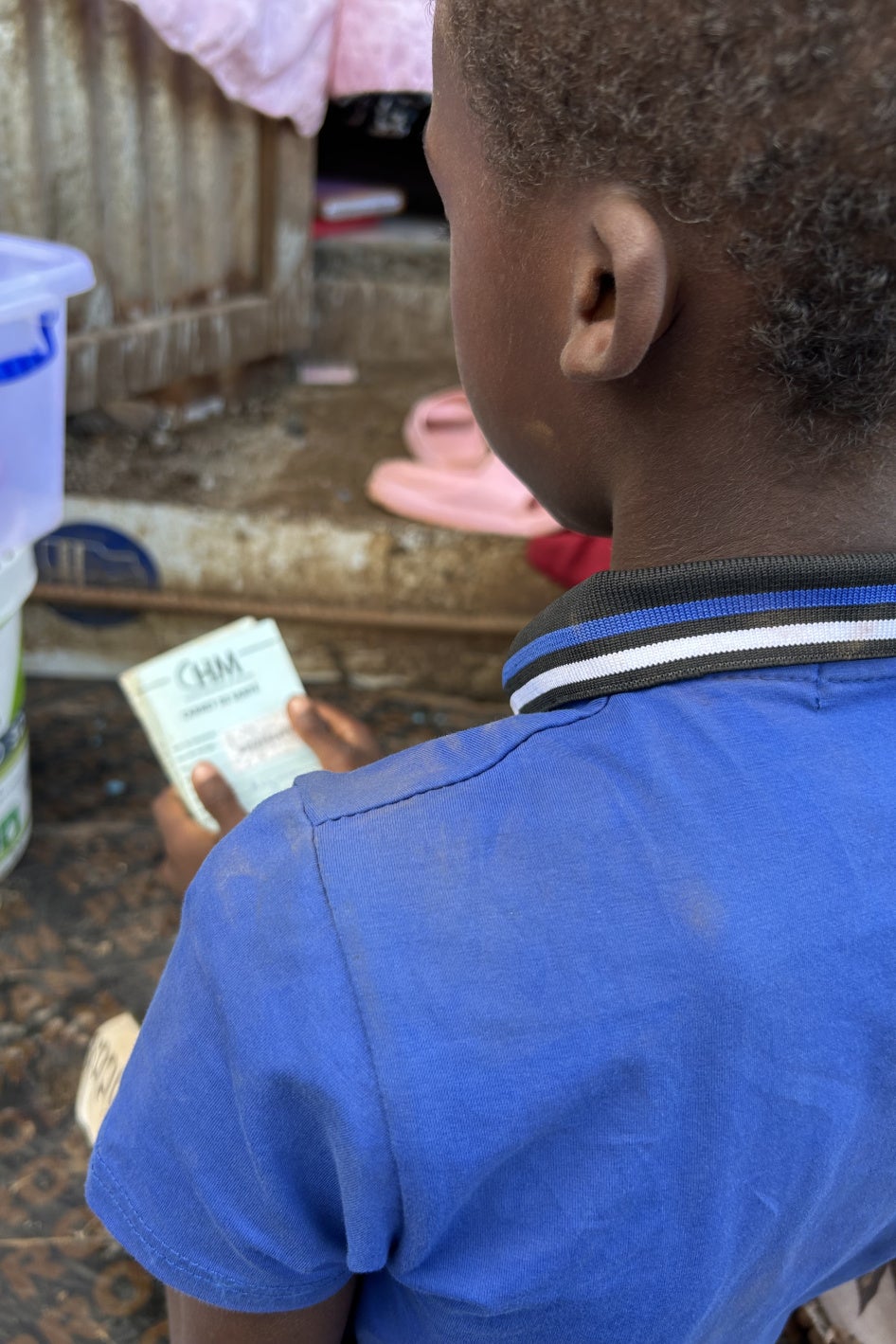

Ismael K., 15, lives in an informal settlement in Mamoudzou, the capital of Mayotte. “We leave our notebooks at school,” he told Human Rights Watch. “If it rains at home, everything gets soaked.” He lives in a banga, an informal settlement largely made up of makeshift shelters made of wood, sheet metal, or tarps. “We don’t have electricity. And water—it’s over there, far away. Every morning, we go down to the public fountain and carry it back in jerrycans.”

Ali F., his friend, added, “Life in a banga is hard. If you haven’t paid for the school lunch, you don’t eat,” he said. “It’s really hard to go to school when you’re hungry.”

Hadidja C., 16, said when she and her brother were younger, “When we were supposed to go to school, sometimes we refused because we were hungry.” She added, “To study at home, we used solar lamps or the flashlights on our cell phones.”

Mayotte, a group of islands located in the Indian Ocean northwest of Madagascar, is one of 13 overseas territories of France, all former French colonies. It is France’s poorest department and one of the most disadvantaged parts of the European Union. More than 75 percent of the population lives below the poverty line. Mayotte also has the highest population growth rate in France, estimated at nearly 4 percent per year, contributing to severe strain on housing, education, and public services. Thousands of children in Mayotte live in informal settlements in makeshift dwellings lacking access to running water, electricity, or sanitation. The French government’s neglect of Mayotte is an ongoing legacy of colonialism that has left the islands persistently underdeveloped, with many of its inhabitants facing insecure housing; inadequate food, health, and social protection; and unemployment.

A prolonged drought has caused frequent water shortages, and a devastating cyclone in December 2024 inflicted widespread damage on homes, schools, and infrastructure.

Mayotte’s education system has for years faced a lack of school facilities and teacher shortages. Although education is free, compulsory between the ages of 3 and 16, and by law should be available to all children in France, a 2023 University of Paris Nanterre study found that as much as 9 percent of Mayotte’s school-age population was not in school. For those who do attend, completion rates are abysmal.

Schools are overcrowded, often operating well beyond their intended capacity. For the last two decades, many primary schools have operated on a “rotation” system, with one group of students attending class in the morning and another in the afternoon. France’s Defender of Rights, an independent national authority for the protection of rights, found in October 2023 that as many as 15,000 children did not have access to a full school day.

Contrary to the norm in French schools, most schools in Mayotte have no canteen and do not offer full lunches, instead providing a small snack, such as yogurt, bread, and fruit. For many students, this may be the only meal of the day. Other children whose families cannot afford the fee for the snacks end up going without food at all.

Half the department’s secondary teachers are on temporary contracts and frequently lack appropriate training. Teaching is often poorly adapted to the local context and does not adequately account for the reality that French is a second language for most students. Children with disabilities receive inadequate support. Students who go on to higher education in metropolitan France or in Réunion, another Indian Ocean island that is an overseas department of France, often find that they are poorly prepared to continue their studies.

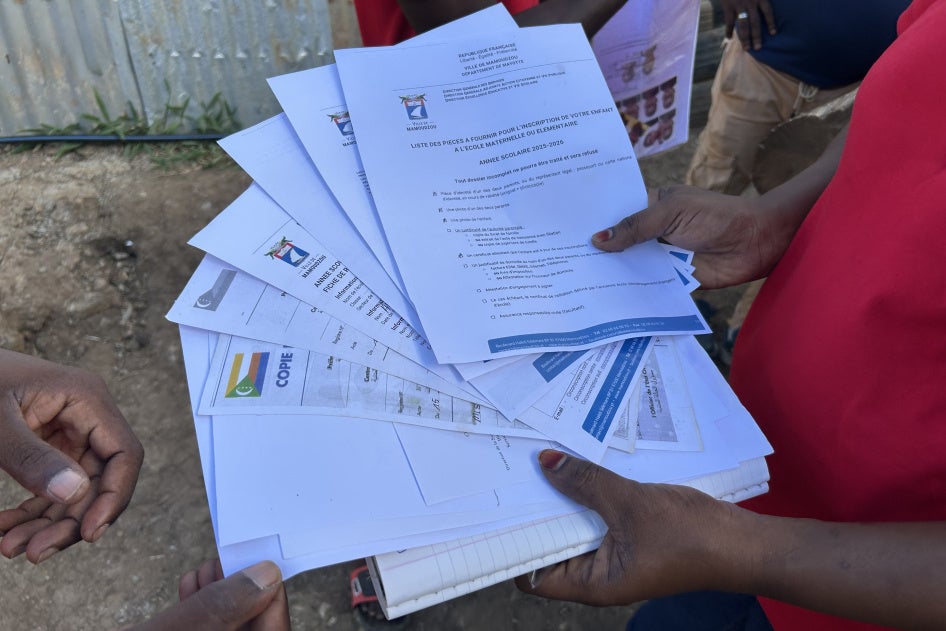

Many children, particularly those living in informal settlements and children from migrant families, face daunting obstacles to enrollment. Municipalities often demand numerous documents, far more than the French education code requires, delaying children’s entry into school and imposing extra expenses many families can ill-afford. These barriers are in part an effort to manage enrollment rates, local officials told Human Rights Watch, in violation of France’s legal obligations to ensure universal access to education.

While migration remains an integral part of Mayotte’s social fabric—shaped by historical, linguistic, religious, and familial ties with the nearby independent island nation of Comoros, which France jointly administered for nearly a century—it has, in recent years, become a source of resentment for many residents and has been politicized in ways that undermine children’s access to education and other public services.

Some municipalities have reportedly resisted building new schools, fearing they would primarily benefit the children of migrants or even draw more irregular migration.

Fear of arrest by border police near schools and municipal offices discourages many undocumented parents from accompanying their children to school or accessing essential public services, including child vaccinations.

Children of asylum seekers and other recently arrived migrants from Central and East African countries, including the Democratic Republic of Congo, Eritrea, Rwanda, and Somalia, had at the time of writing lived for six months in particularly dire conditions months in the Tsoundzou 2 neighborhood of Mamoudzou, in dilapidated tents in an encampment with no toilets for more than 500 residents and no access to education. In late September 2025, authorities announced the dismantling of the encampment, with just over half the encampment’s residents offered alternative accommodation. After authorities demolished the encampment in late October 2025, more than 400 people, including 25 families with children, were left without shelter.

Laws that apply only in Mayotte further marginalize its residents. For instance, the government has twice amended the citizenship laws, in provisions that are applicable just to Mayotte, to make it harder to acquire French citizenship by birth in the territory. Even before these changes, one-third of Mayotte’s “foreign” population was born there.

These laws have profoundly unsettled people who have lived in Mayotte for much or all of their lives, while doing nothing to address high rates of unemployment and poverty, crumbling infrastructure, and overstretched social services.

The serious shortcomings identified in this report are longstanding challenges that violate children’s rights, notably the right to an education. Many of these shortcomings have been identified, in some cases repeatedly, by the Defender of Rights, the National Human Rights Advisory Committee (Commission nationale consultative des droits de l’homme, CNCDH), government inspectors, and the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child.

The response to the devastation of the December 2024 cyclone requires a focus on rebuilding rather than scapegoating. National and local authorities should take reconstruction efforts as an opportunity to correct years of neglect, including of its school system.

To address these human rights violations, municipalities in Mayotte should immediately adhere strictly to the provisions of France’s education code on school enrollment, asking parents only for the documents the law specifies. The prefecture should strictly enforce compliance with this law.

Exceptional laws that apply to Mayotte only for residence permits as well as social protection and labor laws should be abandoned, and Mayotte-specific restrictions on access to citizenship revised to remove arbitrary barriers to children’s access to fundamental rights.

A fuller list of recommendations appears at the end of this report.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted in Mayotte in May 2025, including in the informal settlements in Combani, Kawéni, Labattoir, Mtsapéré, Tsoundzou 1, and Tsoundzou 2. Human Rights Watch interviewed 41 children between the ages of 8 and 17 (14 girls and 27 boys), one 19-year-old who described her recent experience in school, and 9 adults (3 men and 6 women) who had tried to enroll their children in school.

Human Rights Watch met with officials from the prefecture, the rectorate (the education authority responsible for the organization and management of secondary education, or middle and high schools, in Mayotte), and the Mamoudzou and Dembéni mayors’ offices. Human Rights Watch also spoke with teachers, a representative of the teachers’ union, academic researchers, members of associations that provide classes for out-of-school children and support children and families living in informal settlements, as well as unaccompanied children and children with disabilities, and the spokesperson of a citizens’ collective.

Human Rights Watch also analyzed government data and reviewed official documents, including institutional and parliamentary reports, as well as reports issued by the Defender of Rights, the National Human Rights Advisory Committee (Commission nationale consultative des droits de l’homme, CNCDH), the Court of Auditors (Cour des comptes), the Regional Audit Chamber (Chambre régionale des comptes), government inspectors, nongovernmental organizations, and academic studies. This report reflects developments and information available as of October 31, 2025.

All interviews were conducted in French or English, in some cases with Shimaore interpreters. When possible, interviews with children and parents were conducted one-on-one in a private setting. Researchers also spoke with children in pairs or small groups at their request or when time and space constraints made individual interviews impractical. Researchers obtained oral informed consent or assent after explaining the purpose of the interviews, how the material would be used, that interviewees need not answer questions, and that they could stop the interview at any time. Human Rights Watch did not provide interviewees with financial compensation in exchange for any interview.

Human Rights Watch sought comment from the prefecture, the rectorate, and the Dembéni, Dzaoudzi-Labattoir, Koungou, Mamoudzou, Pamandzi, and Tsingoni mayors’ offices. As of October 31, 2025, when this report was finalized for publication, none of these offices had provided comments on our findings or answers to our written questions.

This report uses pseudonyms for all children and parents to protect their privacy. Some teachers and others requested that their names not be used in this report in order to protect their own privacy or the privacy of their students or to allow them to speak freely about their employer.

In line with international standards, the term “child” refers to a person under the age of 18.[1]

I. Legacies of Colonialism

Relations between Mayotte and Paris are hypocritical. Each successive [national] government has been aware of the local reality. But how can we explain that despite these difficulties, Mayotte, the poorest department in France, still lags behind in terms of funding? There is a gap between Mayotte and the other overseas territories, and also with mainland France. . . . Of course, the situation has improved compared to a few years ago. But we are far from what we should have.

— A municipal official interviewed by Human Rights Watch, May 22, 2025

Walking along the steep hillside paths in Tsoundzou 1, an informal settlement on the southern part of Mayotte’s capital, Mamoudzou, an outreach worker described daily life. Children hauled buckets from communal taps at the base of the hill. Most houses lacked electricity. There were no toilets in the community, he said. Many children were not in school, while those enrolled often walked up to an hour each way. “For us it’s just normal,” he said. “But it really isn’t normal—not when you remember that we are in France.”[2]

With its extremely high poverty rate, low standard of living compared to France as a whole, health system at the breaking point, crumbling infrastructure, and sprawling, sordid slums, Mayotte, a group of islands in the Indian Ocean archipelago that also includes the nearby independent Union of the Comoros, is a world apart from the metropole.

The education system is under similar strain, as detailed in this report. “Investment in education in Mayotte is lower than in other territories. Simply bringing it up to standard would already be a step forward,” a representative of the education union told Human Rights Watch.[3] As a teacher observed, “Education is the sector that encompasses all aspects and challenges found in Mayotte: poverty, immigration, access to water, sanitation, lack of equipment, etc.”[4]

Mayotte was a French colony from 1841 to 1974. After a referendum in 1974, Comoros declared independence, but Mayotte, part of the Comoros Islands archipelago, remained French territory. Mayotte became a departmental collectivity in 2001, a French department in 2011, and an “outermost region” of the European Union in 2014.[5] It has the lowest standard of living of any overseas department, and one that is much lower than in mainland France.[6]

The national government’s comprehensive neglect of Mayotte is an ongoing legacy of colonialism. The persistent underdevelopment of Mayotte means that many of the islands’ inhabitants face insecure housing; inadequate food, health, and social security; and high rates of unemployment. Lack of attention to these and other rights have also left Mayotte ill-equipped to face extreme weather events, including a decade-long drought and a devastating cyclone in December 2024 that destroyed homes, hospitals, schools, government offices, and other infrastructure.

Longstanding Neglect

France has severely neglected Mayotte, including through underinvestment in health, infrastructure, education, and housing.[7]

In 2023, 8 out of 10 children in Mayotte lived below the national poverty line, compared to 2 out of 10 in mainland France.[8] Forty-two percent of its population lived on less than €160 (about US$185)[9] per month in 2018.[10] The median standard of living in Mayotte is nearly seven times lower than in mainland France, at just €260 per month.

Data collection in Mayotte remains strikingly limited on key issues such as child malnutrition, school enrollment rates in informal settlements, and access to clean water. These gaps make it difficult to assess needs, design effective public policies, and monitor compliance with France’s human rights obligations.

Lack of Secure Housing

Many people live in informal settlements, known as bangas in Mayotte, often built of scrap materials on dirt floors.[11] In 2017, 4 out of 10 houses were makeshift dwellings, roughly the same proportion as in 1997 but a significant improvement over 1978, when makeshift dwellings were nearly 95 percent of the housing stock.[12]

Some 81,000 people, those living in more than half of Mayotte’s makeshift dwellings along with 12 percent of permanent dwellings, lacked running water at home in 2017. Some used yard taps; others relied on relatives, friends, standpipes, wells, or rivers.[13]

Inadequate Food, Health, and Social Protection

Nearly half the population lacks regular access to food.[14] Ten percent of children aged 4 to 10 suffer from malnutrition.[15]

The health system is under strain:[16] Specialist care is not always available locally, infant mortality is three times higher than in mainland France, and mental health services are weak.[17]

Social protection benefits are less than and labor protections weaker than in the rest of France.[18] Child protection services are “struggling to meet the scale of the need for care,” an interministerial investigation found.[19]

The minimum wage remains lower in Mayotte (€8.98 per hour in 2024) than in metropolitan France (€11.69)[20] even though the cost of living is by most measures higher.[21] In 2022, prices in Mayotte were on average 10 percent higher than in metropolitan France (excluding housing), with especially steep costs for food, more than 30 percent higher than in the metropole.[22]

The 2025 Rebuilding of Mayotte Law accelerates the path toward aligning the minimum wage and social protection benefits with national levels, but full convergence will not be reached until 2031.

Most teachers, doctors, senior government officials, and senior postholders in the largest private enterprises are from metropolitan France.[23] Staff from Mayotte who do substantially the same jobs as metropolitan staff often receive fewer benefits. “There’s extra assistance for mainland French citizens. Housing assistance while locals pay full price. Bonus leave. A third year of bonus after two years of service,” a staff member from a local association working with children told Human Rights Watch, adding, “It’s just like colonial times.”[24]

“Mayotte remains a dual society, with an agrarian subsistence economy existing alongside a service economy driven largely by a growing public sector in which most jobs are filled by metropolitan French,” Nicolas Roinsard wrote in 2012.[25] Ten years later, he observed:

What is generally observed in overseas territories is also true in Mayotte: economic development is exogenous, based on extremely strong ties with mainland France, which provides financial transfers, skills, and jobs on the one hand, and exports consumer goods on the other. In just a few decades, Mayotte has gone from a self-sufficient agrarian economy to a service and import-distribution economy, placing it in a situation of extreme dependence.[26]

As discussed later in this chapter, Mayotte also remains subject to differentiated legal regimes that restrict certain rights, particularly in the areas of immigration, nationality, and housing, despite its status as a French department.

High Unemployment

In 2024, only 32 percent of people aged 15 to 64 in Mayotte were employed. This employment rate is half that of mainland France. The unemployment rate, a measure of the working-age population that is actively looking for work, stood at 29 percent in Mayotte, the highest in France.[27]

High Levels of Insecurity

Insecurity is a serious, longstanding concern. Robbery involving threats or violence was 10 times more likely than in mainland France in 2018 and 2019 and was the most common crime reported in those years. Other types of crime, including burglary of homes and theft from cars, were also much more common in Mayotte than in metropolitan France.[28]

Harsh and Differential Treatment of Migrants

Mayotte’s history and location mean that migration, particularly from Comoros, less than 70 kilometers away, has always been part of the islands’ social makeup. Nonetheless, as Mayotte’s population has grown, public sentiment against migration has increased. Indeed, with almost half of the population foreign nationals, immigration has become the focus of public attention, and officials often blame mass immigration for many or most of Mayotte’s problems. As the French Defender of Rights has pointed out:

[I]f the under-resourcing of Mayotte’s public services is such that it does not allow all those who are legitimately entitled to benefit from them to do so without discrimination, responsibility must be sought on the part of those who are in charge of them and not those who use them. However, on the part of the public authorities, the argument that the proper functioning of public services and the social balance of the island would be jeopardized by mass immigration seems to be widely accepted.[29]

In particular, the state’s response to infrastructure deficits has centered on tackling irregular migration, which risks exacerbating divisions and fueling social tensions.[30]

Local authorities have put in place policies and practices that dissuade some families from enrolling their children in schools. The prefecture (the local branch of the central government representing the state at the departmental level) effectively acquiesced in a monthslong blockade of its offices by a citizens’ collective from October 2024 to May 2025, with the exception of a few weeks after Cyclone Chido, which successfully aimed to foreclose access to the premises for people seeking residence permits based on their family ties in Mayotte and those seeking to lodge asylum claims. The French government, in turn, has responded to irregular migration and the backlash against migrants by enacting legislation that applies only in Mayotte, including Mayotte-specific rules for residence permits, access to citizenship, and immigration enforcement. These measures have affected children’s access to education and their enjoyment of other human rights.[31]

Inadequate Response to Climate-Related Challenges

An Ongoing Drought

Persistent droughts have for years seriously affected access to water. Mismanagement and lack of preparation have exacerbated the crisis.[32]

Running water was cut two out of every three days in late 2023 and early 2024 and then for 26 consecutive hours every two days during much of the 2024 dry season. In late November 2024, authorities announced that the shutdowns would be extended to 30 hours every two days.[33] The government also began distributing bottled water brought in from Réunion, Mauritius, and metropolitan France,[34] although some people who could not provide identity documents, electricity or water bills, or similar documents said they were turned away at distribution points.[35]

Water shutoffs were ongoing in mid-2025.[36]

The December 2024 Cyclone

A devastating cyclone—named “Chido”— ravaged Mayotte in December 2024, demolishing entire neighborhoods and seriously damaging the hospital, airport, port, and government buildings.[37] Thirty-nine of Mayotte’s 221 primary schools were completely destroyed, and 5 of its 33 collèges and lycées (middle and high schools) were significantly damaged.[38]

Describing the immediate effects of the cyclone, the editors of Plein Droit, a magazine focusing on migrants’ rights, wrote:

Chido has left the island in a state of ruin. Individual houses and public buildings have been partially or completely destroyed, often flooded—and of course even more so the precarious dwellings known as bangas, made of wood and sheet metal—streets are littered with debris, trees and poles are lying on the ground, and fields and vegetable gardens have been laid bare. Water, electricity, and telecommunications services have been cut off, shops closed, and public services paralyzed.[39]

The destruction of trees and vegetation severely affected residents’ livelihoods and food security, as fruit trees, gardens, and small-scale farms—key sources of income and daily sustenance for many households—were destroyed.

Though informal settlements were hit particularly hard by the cyclone, initial aid efforts neglected those areas.[40]

In the first months of 2025, the cyclone’s impact on education was severe. Thousands of children were unable to resume classes when schools reopened in January, with many establishments closed or operating in heavily damaged buildings. Classes were frequently held in shortened schedules or relocated to temporary sites such as neighboring schools, community halls, or tents. Teachers described overcrowded conditions, with two groups of students often sharing a single classroom. Significant delays in the repair of infrastructure meant that normal timetables could not be maintained for much of the school year’s first semester.[41]

In August 2025, eight months after Chido, the start (rentrée) of the 2025-2026 school year remained marked by disruptions. The authorities described the rentrée as “satisfactory,”[42] stating that most students were able to return to class despite the destruction of dozens of schools. Nonetheless, some schools were unable to reopen,[43] and many others operated in temporary facilities. In primary schools, most children were able to receive close to the standard 24 weekly hours of instruction, but only through rotation systems—sometimes with up to five different groups of students using the same classroom in a single day.[44]

About 8 percent of primary school students had between 10 and 20 hours of class per week, and some students received fewer than 10 hours of class each week, according to news accounts.[45] Lessons often took place in prefabricated classrooms, shared premises, or tents, with limited equipment and in some cases inadequate sanitary facilities. Local authorities pointed to progress compared to the previous semester, while teachers and parents emphasized the continued challenges for children’s schooling.[46]

II. Barriers to Education

More than 1 out of every 3 people in Mayotte is of compulsory school age.[47] By French law, children’s education is free and compulsory between the ages of 3 and 16, and available free until the end of secondary school, including in Mayotte. Yet, a 2023 University of Paris Nanterre study found that between 5,379 and 9,575 children aged 3 to 15 were not enrolled in school, representing between 5 and 8.8 percent of children.[48]

The high proportion of children not in school is the result of a variety of factors, including insufficient educational infrastructure, onerous—and illegal—enrollment requirements, food insecurity, and safety concerns. Children whose first language is not French face additional barriers.

Moreover, the cumulative impact of repeated disruptions, including the Covid-19 pandemic, large-scale evictions (described more fully in the next chapter), and Cyclone Chido, has resulted in “enormous learning deficits” for many students, an aid worker told Human Rights Watch.[49]

Every child has a right to a quality and inclusive education, which allows them to develop to their fullest potential, and provides them with the skills and experiences necessary to thrive in today’s world, including through finding or creating meaningful employment opportunities that will allow them to avoid or escape poverty.[50] In contrast, inadequate access to education leads to diminished opportunities,[51] risking the perpetuation of the extreme poverty that characterizes Mayotte’s numerous informal settlements. As one youth said, “When you don’t go to school, you’re left standing on the side of the road.”[52]

Both government officials and residents of informal settlements frequently expressed concerns to Human Rights Watch that lack of access to education could also lead to increased delinquency. In a comment typical of those we heard, a senior official at the prefecture said, “A child who does not go to school is a potential future criminal. This is something we have created in the past and must now deal with. It has created insecurity.”[53]

Such concerns are understandable in a context in which one in ten people has experienced violent crime within the previous two years and crime rates are three to four times higher than in metropolitan France.[54] As the sociologist Nicolas Roinsard explained when Human Rights Watch spoke with him in April, inadequate access to education can fuel a cascading cycle of exclusion, in which school dropout triggers wider social rupture. Some children face multiple vulnerabilities, including family breakdown, the isolation of single mothers, and the threat of deportation, which place them particularly at risk of marginalization or integration into delinquent networks.[55]

Obstacles to Enrollment

Many municipalities have imposed onerous, illegal requirements for school enrollment. By law, children should be enrolled after showing proof of children’s identity, the identity of an adult responsible for the child, and the child’s residence in the municipality,[56] with the possibility of presenting declarations for any of these three elements if other documents are unavailable.[57]

In practice, however, municipalities require many parents—particularly those living in informal settlements or who are migrants—to produce numerous additional documents, often at a cost they can ill-afford and which they can acquire only after considerable delay, if at all. Undocumented parents also risk apprehension and deportation as they apply for the documents they need to enroll their children or as they take younger children to and from school. These requirements have the apparent purpose of reducing enrollment numbers, particularly the enrollment of children living in informal settlements, whose parents are often undocumented.[58]

Describing his efforts to register three of his children in school, Saïd N., from Comoros, said that he had made four or five trips to government offices to obtain the documents municipal authorities required, beginning the process in August 2024. “It takes me five hours on foot to go and come back,” he said. Months later, he had not succeeded. “The mayor’s office told me the oldest boy, he’s 10, is too old to be registered for school. They say the other two need vaccination cards.”[59] His wife, Fatima, added that when she accompanied him on their most recent attempt to enroll their children, “the officials told me to return to Comoros and put the children in school there.”[60] As of May 2025, the children were still not enrolled in school.

Human Rights Watch heard numerous accounts of children who were unable to enroll because local authorities demanded documents in addition to those required by law or simply had not responded to their attempts to register for school. For instance:

Ismael A., 14, said, “I’ve never been to school. I was born in Mayotte, but I don’t have a birth certificate, so I couldn’t enroll.”[61]

Aboubacar S., who gave his age as 14 or 15 and said he was also born in Mayotte, told us he had not been able to register for school because he lost his birth certificate in a fire.[62]

Mahamoud H., 17, told Human Rights Watch he and his mother had submitted his documents in March 2024, when registration for the 2024-25 school year opened, and was still waiting for a response in May 2025.[63]

As with Saïd and Fatima’s children, many municipalities demand proof of vaccination even though that is not among the legal requirements for school registration.[64] While child vaccinations are obligatory in France, children and their parents have three months after school enrollment to provide them. Assessing the legislative framework, the Defender of Rights has cautioned that the lack of vaccination documents should not be a barrier to school registration.[65]

Some municipalities only accept birth certificates issued within the previous three months, a rule that poses particular challenges for children who were born in Comoros or other countries.[66] Other documents demanded by some municipalities have included current proof of social security, a certificate from the Family Allowance Fund (Caisses d’Allocations familiales, CAF), the most recent tax bills sent to parents as well as to landlords, and the physical presence of the landlord.[67]

Proof of residence can be particularly challenging for families living in informal settlements, which do not have recognized addresses. Amina F., 35, explained that landowners “build or allow others to build bangas on their land and charge rent. Since it’s not declared, they don’t want to give us an address.”[68]

Municipal authorities do not usually allow children to submit sworn statements if they do not have birth certificates, as in Ismael’s and Aboubacar’s cases. In practice, getting a new birth certificate requires documents that children and their parents may not have. A volunteer explained, “To obtain a birth certificate, you need an ID or the old one. But some children have neither.”[69]

Municipal officials interviewed by Human Rights Watch insisted that they followed the law. For instance, the Mamoudzou mayor’s office told Human Rights Watch:

The law is strictly enforced. It’s an absurd law. But it’s the law. . . . We know that the vast majority of documents are false, but we register the children anyway. This is very problematic because we have no certainty about the identity of the child or the guardian. We have no address. We have no way of contacting them if a child is injured, for example. If the child is sick, who do we contact?[70]

Similarly, an official in the mayor’s office of Dembéni, Mayotte’s fourth-largest municipality, said that his municipality enrolled children “regardless of their parents’ situation. Everyone is enrolled.” However, he said:

We can speak of two categories of children: 1) young French nationals with legal status (whose [non-citizen] parents have a residence permit), and 2) young people whose parents are undocumented.

In terms of schooling, the law is the same as in mainland France. However, in practice, elected officials differentiate between young people in the first category and those in the second category.[71]

In fact, when the Regional Audit Chamber (Chambre régionale des comptes) reviewed 13 of Mayotte’s 17 municipalities between 2022 and 2024, it found that “most municipalities impose highly discriminatory enrollment conditions. While these measures help regulate capacity constraints, between 3,000 and 5,000 school-age children do not benefit from compulsory education.”[72]

One consequence of this approach is that it puts additional pressure on the child protection system, which can intervene to ensure that children receive an education. A senior official with Mayotte’s child protection services explained:

A significant number of young people and families are dependent on child protection services as their only chance to benefit from children’s rights. This is because schooling is problematic. Municipalities use administrative barriers to justify their inability to provide schooling to everyone. . . . Normally, a sworn statement from the parents is sufficient for enrollment. However, in practice local authorities do not accept this. Children are referred to the ASE [l’Aide sociale à l’enfance, the child protection system] because that way they are protected and are enrolled in school. The ASE has become the means of accessing education.[73]

Children whose parents are undocumented are disproportionately likely to face obstacles to enrollment. Even so, some officials suggested that these problems were not necessarily the result of discrimination. An official in the Dembéni mayor’s office told Human Rights Watch:

Proof of eligibility is required for enrollment. French nationals have the necessary documents. However, despite this, there are children who are not enrolled in kindergarten because there are no places available. Even French children do not have a place. This cannot be considered discrimination because even French nationals do not have a place. There are no places available for children under the age of 4.[74]

In fact, some of the excessive documentation requirements are imposed only on children whose parents are not European Union nationals, the Regional Audit Chamber and the Defender of Rights have found. As an example, one municipality, Chirongui, in the southern part of Grande-Terre, required that for non-EU nationals, “the landlord can only host one family” each year and if the child’s parents are not in Mayotte, the child must submit “a parental authorization form from the French embassy in their country of origin or a guardianship document.[75]

The Regional Audit Chamber and the Defender of Rights have found that municipal demands for documents not required by law “aim in particular to prevent the most vulnerable groups from attending school: children of parents in an irregular situation, unaccompanied minors without a guardian.”[76]

We asked officials why they thought barriers to enrollment persisted. One noted that although the prefect could compel a municipality to register children, undocumented parents would almost certainly be unwilling to make a complaint to the same government office that oversees the border police. “There is also the risk of resistance from the Mahoran population,” the official commented, using the term for Mayotte’s inhabitants that has come to refer to longstanding residents who are French citizens.[77]

Another official explained:

There are not enough classrooms to accommodate everyone. As a result, elected officials request a large number of supporting documents for enrollment, such as proof of address, valid residence permits, etc. . . . The real problem here is capacity. If we don’t register the French children, we are condemning them permanently because they can’t go anywhere else. Whereas we can consider that the others [the children of undocumented parents] had the option of staying where they were. So the elected representatives of Mayotte find themselves in a terrible dilemma. A choice has to be made. That doesn’t mean it will be the best choice.[78]

Insufficient Infrastructure

The high proportion of children not in school is in part the consequence of an insufficient number of schools. Class sizes are large, 30 or more in some primary schools as compared with an average of 22 in metropolitan France;[79] collèges and lycées often have three to four times more students per class than those in metropolitan France.[80] Municipalities, which are responsible for primary education, have for more than two decades run many schools on a “rotation” system, meaning that most students in Mayotte attend class either in the morning or the afternoon only.[81] Since Cyclone Chido, some schools have three rotations each day, and in some cases this can go up to five.

The lack of capacity of its educational system is a longstanding, well-known, and worsening problem.[82] With more than 321,000 inhabitants in 2024, Mayotte’s population has nearly quadrupled since 1985, making it France’s fastest-growing department. Half the population is under 18, and fertility rates are France’s highest, with an average of nearly 4 children per woman, compared to 1.8 in mainland France.[83]

The Ministry of Education has estimated that Mayotte needs more than 4,000 additional classrooms to keep pace with its expected population growth in the coming years.[84]

At the beginning of the 2024-2025 school year, the department had 71 écoles maternelles, schools for students between the ages of 3 and 6; 150 elementary and primary schools, which students attend for five years; 22 public collèges (the following four years, beginning with 6ème, equivalent to Grade 6 in North America or Year 7 in the United Kingdom, and progressing through 3ème, Grade 9/Year 10); and 11 lycées and polyvents (high schools and polytechnic schools, which students attend for a further three years, known as seconde, première, and terminale).[85]

The rotation system is a stark indication that the existing infrastructure is insufficient for the current number of students. The Dembéni mayor’s office explained:

All school groups in Dembéni operate on a two-shift system. Despite this, we have not been able to enroll everyone. Children are on waiting lists or registration lists, often at the kindergarten level. For children under four years old, there’s just no space.[86]

The number of weekly hours of instruction is meant to remain equal to schooling in mainland France. The department’s new rector, appointed in June, has stated that at the start of the 2025 school year, 90 percent of children in primary education were receiving the standard 24 hours of instruction per week.[87]

In practice, however, the use of the rotation system lowers the quality of education. An inter-ministerial inspection in 2022 found that more than 20,000 pupils attended classes under the rotation system and that afternoon sessions were much less effective because of the difficulty students faced in maintaining focus.[88] Researchers have also found that the system is ill-suited to children’s rhythms and Mayotte’s climatic conditions,[89] while UNICEF France noted in 2023 that rotations struggle to provide quality education, particularly given the lack of after-school opportunities.[90] In 2025, the Regional Audit Chamber reported that 57 percent of children in the communes it audited were still taught in rotations, and that no pedagogical evaluation of the system had ever been carried out.[91]

Assessing all of these factors, the Defender of Rights has concluded that the rotation system violates the right to education and is a breach of equality with pupils in mainland France.[92]

Officials in the Mamoudzou mayor’s office said that the rotation system is particularly problematic because of the lack of safe, structured activities during the part of the school day when children are not in class:

In terms of teaching, half a day would be feasible if significant resources were available for after-school programs. The difficulty is that there is teaching time during the school day and nothing after school. Resources are far too limited for after-school programming. Childcare is provided by adults with little training. There are no activities for children.[93]

To address the shortage of early-grade classrooms, and in addition to the rotation system, the rectorate (the authority that oversees secondary education in Mayotte) introduced an alternative schooling arrangement in 2021, offering to host children for a few hours per week in “itinerant classes,”[94] set up either within a school or another location. The Defender of Rights has criticized this ongoing approach as a violation of children’s right to education and a breach of the principles of equality and nondiscrimination in access to public education because children placed in itinerant classes receive only a few hours of instruction per week instead of full-time schooling. In March 2025, the rectorate stated that these classes provided between 6 and 13 hours weekly; in practice, the number of hours varies by municipality, with some children receiving as little as two effective hours, as found by the Defender of Rights.[95]

Assessing the various stopgap measures authorities have implemented, UNICEF France concluded:

In Mayotte, the rotation system and “itinerant classes” are attempting to address the mismatch between supply and demand for schooling. However, these measures are struggling to meet the challenge of providing quality education, particularly given the lack of extracurricular activities and community education programs. Finally, the enrollment of all children in school is also dependent on access to housing, school transportation, and school meals. These services are both essential for school enrollment and a powerful lever for reducing inequalities.[96]

An official from the Mamoudzou mayor’s office stated, “When we say we welcome all children, it’s not true. With three rotations per day, we can’t say we’re educating.”[97]

The August 11, 2025 law on the Rebuilding of Mayotte provides for ending school rotations and itinerant classes by 2031.[98] However, one official from the rectorate expressed doubt that there would be enough schools to accommodate all children by then, particularly given the rapid demographic growth.

France’s National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques, INSEE) has refuted claims that its population statistics do not adequately account for irregular migration and residence in informal settlements. Nonetheless, in an indication of how contested official population figures are, the August 2025 reconstruction law to respond to the damage from Cyclone Chido requires a comprehensive census of Mayotte’s population by the end of the year.

An emergency plan in effect between 2014 and 2020 aimed to create between 400 and nearly 600 additional classrooms and renovate 150 primary schools. Delivery on the plan fell far short of its promise, yielding only about 120 classrooms.[99]

Some municipalities are reluctant to invest in infrastructure that is perceived primarily as benefitting migrants, the Court of Auditors (Cour des comptes) found in 2022.[100] A high official from the prefecture interviewed by Human Rights Watch described this dynamic:

There are difficulties with certain elected officials regarding schools. Several of them do not want to build schools. This is acknowledged. For them, a school means an influx of illegal immigrants into the community. In the south, a mayor wants to build an artist’s residence on the last available plot of land, even though it is the only possible site for a school.[101]

Lack of Support for Children Facing Difficulties in French

French is a second language for much of Mayotte’s population. In addition to being the sole official language since Mayotte became a department in 2011, French coexists with two recognized regional languages, Shimaore and Kibushi.[102] Less than 30 percent of adults under the age of 65 use French on a daily basis to communicate with their family and friends, and almost half do not understand French.[103]

Young people in Mayotte are more likely to speak French. Even so, just under half of youth between the ages of 18 and 24 had difficulty writing in French, INSEE found in a 2022 survey.[104]

A dedicated agency, the Academic Center for the Education of Newly Arrived Allophone Students and Children from Itinerant Families and Travelers (Centre académique pour la scolarisation des élèves allophones nouvellement arrivés et des enfants issus de familles itinérantes et de voyageurs, CASNAV), evaluates the French language skills of asylum-seeking, migrant, and other children who have recently arrived in French territory.[105]

In principle, newly arrived children of school age who do not have a sufficient command of French to attend regular classes are eligible for French-language lessons through the CASNAV. “Sometimes this takes time. There may not be enough places, or the child’s level does not correspond to the child’s age,” said an official from Mayotte’s child protection services.[106]

As elsewhere in France, the work of CASNAV in Mayotte is focused on children who have recently arrived. In Mayotte, however, French is a second language for much of the locally born population.[107]

As a teacher of French and FLE (French as a Foreign Language) observed, “The rector refuses to take into account a student’s mother tongue even when it has been recognized as a regional language.”[108]

Mayotte has the worst educational outcomes in France.[109] It has the lowest performance in national assessments of mathematics and French[110] and has consistently experienced low success rates on the diplôme national du brevet (DNB) and the baccalauréat.[111] Christine Colombiès, with the University of Rouen’s Research Group on Multilingualism in Mayotte (Groupe de Recherche sur le Plurilinguisme à Mayotte), observed in 2009: “One of the causes of significant academic failure is undeniably linked to [the] lack of [French] language proficiency.”[112] More than 15 years later, educational outcomes remain largely unchanged, suggesting that her findings remain relevant.

Although some measures have been adopted in recent years to better take into account Shimaore and Kibushi in education, including a 2021 law on the protection of regional languages,[113] multilingualism is poorly reflected in the education system in Mayotte, teachers told Human Rights Watch.

One teacher told us:

In 2021, Shimaore and Kibushi became regional languages. Shimaore should therefore be taught in schools. But this is not the case. . . . There is not enough research and training on multilingualism.[114]

The failure to support these students, to provide appropriate teacher training, and to recognize the region’s linguistic diversity makes learning extremely difficult for students and poses additional challenges for educators.

The experiences of other French overseas territories show that bilingual curricula lead to better academic outcomes. In New Caledonia, a French overseas territory in the southwest Pacific Ocean, which has made efforts since 2002 to introduce Kanak languages into primary schools, students who have taken part in the bilingual curriculum have shown significantly greater academic progress than students taught only in French, and both groups of students have reached equivalent levels of performance in French.[115]

The Court of Auditors noted that “[i]mproving consideration of the population’s multilingualism . . . will be decisive.”[116]

The island faces severe challenges in attracting and recruiting teachers. In 2022, 50 percent of secondary school teachers were contract workers,[117] as compared with less than 10 percent nationwide.[118]

In May 2025, in response to the declining attractiveness of the teaching profession across France, the French government lowered the qualification required to sit the internal primary school teachers’ competitive exam to the third year of university study. An exception was introduced for Mayotte, where candidates may qualify after two years of study. This measure illustrates the different standards applied in Mayotte. An official from Mamoudzou’s mayor’s office told us:

Faced with these difficulties, we adapt the recruitment level: Bac +2. There is a discrepancy in the requirements depending on the territory. . . . We are seeing the level go down. Mayotte is now seen as a starting point in a career, whereas 30 or 40 years ago it was considered a post for those nearing the end of their career, so the teachers were good.[119]

A teachers’ union representative made a similar point: “Now we hear they are lowering the required qualification from Bac +3 to Bac +2 to become a teacher. This reflects the mentality of our compatriots in mainland France, who look down on the Mahoran population.”[120]

In October 2025, teachers and school staff protested after hundreds of them had gone for months without being paid or receiving only partial payments, pushing some into precarity.[121]

Food Insecurity

It’s very hard to go to school when you're hungry.

— Abdou M., 17, interviewed in Kawéni, May 13, 2025

Unlike metropolitan France, where children receive a full lunch complying with nutritional and other requirements,[122] most schools in Mayotte do not operate canteens and instead provide only a small snack. In Mamoudzou, “the snack is not a full meal; it is a piece of fruit with a small roll, for example,” an official with the mayor’s office told us.[123] Yet, many children who live in informal settlements do not get enough to eat, meaning that the food provided at school is an important part of their daily nutritional intake. These snacks are usually only available to students whose families can pay an annual fee, about €30 to 50, depending on the municipality.

“You always have to pay to be able to eat,” Hadidja C., 16, told us. “It’s hard when you wake up, you’re hungry, and you want to go to school. We go to school from 6 a.m. until 5 p.m. without eating.” Describing the snack that is available to students who can afford the fee, she said, “At 11 a.m., you get a piece of bread, a yogurt, or whatever. That’s what you eat. . . . If you don’t pay, you don’t get anything. All you can do is drink tap water.”[124]

Children told Human Rights Watch that the food they received at school was a significant part of their diet. “Since Chido, we haven’t had anything to eat. My parents can’t find any rice. One day we eat, one day we don’t. It’s every other day. I eat my snack at school. It’s an apple, with bread and sometimes chocolate. And milk,” said a 12-year-old girl.[125]

These accounts are not anomalies. A 2019 study by Mayotte’s public health authority (Agence régionale de santé de Mayotte, ARS) and the rectorate found that one child out of five received just one meal a day.[126]

Hunger affects children’s school performance.[127] A 16-year-old girl told us, “We had nothing to eat. When we had to go to school, we sometimes refused because we were hungry.”[128] An aid worker said, “Children do not eat three meals a day. In terms of learning quality, this is not at all adequate.”[129] Similarly, an official in the Mamoudzou mayor’s office said, “The children sleep a lot in class because they haven’t eaten. They can’t keep up.”[130]

When we asked the Mamoudzou mayor’s office about the fee, they told us:

Schools provide snacks for children who pay. The cost is 31 cents per meal, just recently increased to 40 cents. It’s a small amount, but when you’re billed the total cost for the year and have to pay that amount for several children, it’s difficult for many families. So some children don’t eat.[131]

An inter-ministerial inspection found that one out of three students in Mamoudzou did not receive a snack at school because their families could not afford the fee.[132]

Threats to Safety

School buses are regularly targeted for stone-throwing attacks by groups of local youth which have shattered windows and caused injury to students and drivers. A senior official at the prefecture explained:

Stone throwing is mainly directed at buses from neighboring villages. . . . There are intergenerational conflicts and friction between villages. The vocational high school in Combani is often targeted because it is attended by children from all the villages.[133]

One girl told Human Rights Watch she stopped going to school in 2024, when she was 15, after her bus was repeatedly attacked. “I asked the school administrators to find a solution, some way of going to school that didn’t make us face a barrage of stones, but they said the bus was our only option,” she said.[134]

News accounts illustrate the extent and impact of stone-throwing attacks on buses:

In February 2025, a school bus driver suffered a head injury after his bus was stoned, one of several such incidents in the same week.[135]

A stone-throwing attack on a school bus in Tsoundzou 1 in May 2024, reportedly the 11th such incident in a 10-day period, destroyed several windows.[136]

In a single day in April 2024, 19 buses were stoned, including 13 in Tsoundzou 1.[137]

A December 2023 post by the news channel Mayotte la 1ère showed a school bus with a shattered window and glass scattered over the seats as the result of a stone-throwing incident. One student told reporters, “One of our friends had already experienced this kind of situation, she told us to crouch down.”[138]

“Every morning, when we see the children getting on the bus, the parents are scared: Will the bus be stoned? It’s the same thing every day,” a bus driver told the news program Europe 1 in April 2023.[139]

“According to numerous testimonies, this is very problematic for young students who are afraid to take school transportation and get harassed,” Gilles Séraphin, a University of Paris Nanterre professor who has researched access to education in Mayotte, told Human Rights Watch.[140]

Between one-third and one-half of Mayotte’s school buses have had plexiglass windows installed to better protect students, according to a senior official at the prefecture.[141]

Children with Disabilities

Saïd N. told Human Rights Watch he had painstakingly gathered the documents to request support services for his 4-year-old son, who lives with a disability. “I submitted all the papers nine months ago. The agency has not responded. I’ve heard nothing,” he said, speaking to us in May 2025. He showed a letter dated August 13, 2024, confirming receipt of his complete application. “The last thing they told me was the day I gave them everything. They said no further documents were needed, and I should wait for them to contact me. I’m still waiting.”[142]

Many children with disabilities receive inadequate support in Mayotte, the result of a combination of institutional neglect, an ineffective system for identifying disabilities, lack of trained staff, poor infrastructure, and the effects of immigration enforcement. In 2023, according to the study conducted by Gilles Séraphin, at least 500 children with disabilities were out of school.[143] Ensuring that children with disabilities are enrolled in school and that accommodations are put in place according to their needs is an obligation that falls both on the department and on the rectorate.

In order for a child to receive support at school, a child’s family needs an approval from the Departmental Office for People with Disabilities (Maison départementale des personnes handicapées, MDPH), and according to an official from the Mayotte rectorate, MDPH is lacking behind in issuing official notifications recognizing the child’s disability and specifying the support or accommodations (such as assignment of a disability support worker (accompagnant d’élève en situation de handicap, AESH), placement in a special needs class, or financial support), leaving many children with disabilities without the necessary support:

The MDPH is not functioning properly and therefore the rectorate does not receive notifications of children with disabilities. Only 1 percent of students are registered in Mayotte [as having a disability], compared to 6 percent in mainland France.[144]

In 2025, the Ministry of Education told the Defender of Rights that more than 800 applications were pending at the MDPH, which had not convened a rights allocation committee for over a year.[145]

An education inspector explained, “There is a significant shortfall in early identification. For example, there are fewer than 5 students per social inclusion unit [in Mayotte], whereas the norm [in France as a whole] is 14: 13 for collège and 15 for lycée.”[146] Educational programs for students with disabilities, known as “localized units for school inclusion” (unités localisées pour l'inclusion scolaire, Ulis) consist of small groups integrated into ordinary schools, with students spending part of their time in mainstream classrooms.[147]

Even when the MDPH issues notifications, the shortage of disability support workers (AESH) means that many children still do not receive the support to which they are entitled.[148] AESH are in-class support workers assigned to an individual student with disability or to a group of students.[149]

“There are difficulties in obtaining an AESH [in school],” a representative of the Defender of Rights told us.[150]

For their part, teachers interviewed for this report said that schools are unprepared to support children with disabilities. “We have children with autism. There are no specialists to help them at school. There are problems with support for all disabilities. For example, a child in a wheelchair cannot access the classrooms at the high school in Mamoudzou,” a teacher’s union representative said.[151]

A teacher described his experience with students with learning disabilities:

I have a student who has concentration problems and is probably hyperactive. In the collège, there are lots of students with specific conditions. But there are no resources to deal with them and no screening, so we just pretend there’s no problem. . . . Those who have disabilities, or maybe learning deficits, are enrolled in school but don’t receive any support. Often, these are kids who accumulate gaps in their knowledge. We’ve seen this happen, for instance students who can’t recognize numbers.[152]

The lack of specialized staff also means that mental health needs and other health needs are often unaddressed in schools, an issue that has become particularly acute since Cyclone Chido, which caused severe trauma among children[153] and exacerbated conditions that were already widespread on the island.”[154] The teacher told us:

Mental health is one of the real problems. There are five school psychologists on the island, with 30 schools. So we get one day a week. There is no social worker, another real problem. Apparently, the position isn’t being filled. There aren’t enough nurses. One covers middle school and high school. Staffing levels aren’t commensurate with the size of the population. All our schools have more than 2,000 students. Social workers are often not available because they have a lot of work. Psychologists come one day a week.[155]

Undocumented families face the additional risk of arrest and deportation when travelling to or from the hospital. “Children of undocumented parents have the right to emergency care at the hospital,” said a staff member at an association providing services to children with disabilities. Nonetheless, “even traveling to the hospital is something they sometimes don’t dare to do. The father of a child with multiple disabilities was arrested this morning and sent back to Comoros.”

Cases like this are not isolated, she said. For instance:

In another case, a woman was arrested one evening and scheduled for deportation with her daughter the following morning. After authorities ignored her requests for specific assistance for her daughter during the expulsion, the girl had an epileptic seizure. The woman and her daughter ultimately obtained residence permits after the woman filed a complaint about their treatment by border police.

French border police arrested a third woman in 2023 as she was trying to buy medication for her son at a pharmacy. “We were able to secure her release from detention but could not obtain an appointment with the prefecture to seek her regularization because of the blockade of the prefecture,” the staff member said.

Most of the children the association supports live in informal settlements, this staff member told Human Rights Watch. “Many are living with severe disabilities, so schooling is complicated,” she said.

Changes in eligibility for residence permits, discussed in the following chapter, have impeded the association’s efforts to support children with disabilities. “Parents are no longer able to obtain legal status. We are unable to renew their residence permits. They no longer have social security coverage. So they cannot buy diapers or medicine for their children. They cannot pay,” she told Human Rights Watch. She added, “Those who have legal residence or entitled to social security have access to healthcare. However, they are rarely able to pay for the treatment prescribed.”[156]

III. Exceptional Migration Policies Hinder Access to Education

All children in the Republic are equal under the law. In Mayotte, however, inequality between children has been reintroduced and reinforced based on their parents’ status. There is no equality at birth, and this affects education.

— Gilles Séraphin, professor at University of Paris Nanterre, interviewed by the publication La Croix L’Hebdo, June 21, 2025

Mayotte-specific legislation has restricted eligibility for residence permits and citizenship, creating uncertainty and insecurity for many children and parents who would be eligible for regular migration status elsewhere in France. Migration enforcement operations, notably large-scale evictions in 2023 and 2024, and the acquiescence of the prefecture in a months-long blockade of its immigration office have added to these concerns. Inadequate reception infrastructure for the several thousand asylum seekers who arrive in Mayotte each year has meant that asylum-seeking families face particularly dire conditions.

These laws, policies, and practices have contributed to the barriers children face in access to education. Parents at risk of document checks often fear going to government offices to obtain the documents required to enroll their children or may be unwilling to take children to and from school. Children told Human Rights Watch that concerns about being able to continue their education after secondary school and the fear of being undocumented at age 18 made it hard for them to focus on their studies and led them to question the value of continuing in school. Children in asylum-seeking families had not attended school at all during their time in Mayotte, in some cases eight months or more, families and case workers told us.

Legislation Applicable Only to Mayotte

France’s constitution allows for special measures for overseas departments and territories.[157] Migration laws in particular have often included Mayotte-specific provisions. For example, residence permits issued in Mayotte are valid for that department only, a restriction that the August 2025 Rebuilding of Mayotte Law set to end in 2030. Travel to another part of France, including nearby Réunion, requires a visa. Residence permits are subject to additional eligibility requirements in Mayotte.

French lawmakers have also imposed limitations on the droit du sol, the principle of citizenship by birth in French territory, in provisions enacted in 2018 and 2025 that applied only to Mayotte. After a May 2025 reform, a child born in Mayotte can only claim French nationality if both parents held regular status—either a residence permit or French citizenship—for at least one year prior to the child’s birth. If the child lives in a single-parent household, the new requirement applies only to that parent.[158]

As a result, for a child born in Mayotte, successive legal changes mean their year of birth and the migration status of their parents at the time of their birth affect their eventual eligibility for French citizenship or a residence permit.

These measures have been complemented by a host of other exceptional provisions relating to health, freedom of movement for children, identity checks, and restrictions on guarantees in deportation proceedings that treat Mayotte differently from the rest of France.[159]

Many families in Mayotte include a mix of French citizens, residents with permits of varying lengths of validity, and undocumented adults.

Moreover, the Defender of Rights has found that Mayotte’s civil registry imposes unlawful hurdles for non-French parents seeking birth certificates for their children born in Mayotte, leaving children unable to prove citizenship or residency rights.[160]

Such special provisions are frequently justified as deterrence of migration. A 2014 Ministry of the Interior report said that the differences from ordinary law were aimed “to discourage illegal immigration as much as possible, particularly of minors.”[161]

A volunteer described the negative impact: “We are preventing an entire generation of young people born in Mayotte from making plans for their future in the territory. France has invested in their health and education, but [then says], ‘No, you’re Comorians.’ It’s cynical and inhumane. When it’s obvious that this won’t reduce the influx.”[162]

Immigration Office Regularly Blockaded

We have been blocking the prefecture for eight months. We only took a break after Cyclone Chido. . . . . A few weeks ago, we realized that the prefecture had opened a foreigners’ office in a school to get around our blockade. We went there and threatened to block everything. That office has now closed.

— Spokesperson, citizens’ collective, May 12, 2025

Members of a citizens’ collective, the Collective for the Defense of the Interests of Mayotte 2018 (Collectif pour la défense des intérêts de Mayotte 2018) or simply Mayotte 2018, blockaded the entrances to the prefecture’s office in Mamoudzou from October 2024 through May 2025.[163] The collective’s spokesperson told Human Rights Watch that the blockade was in part motivated by concerns that migration led to overcrowding and crime in Mayotte.[164]

During the blockade, asylum seekers could not lodge claims and people could not obtain the visas they needed to travel elsewhere in France, including to continue their studies.[165]

The prefecture arranged alternate locations for people to pick up residence permits during the blockade, but several hundred asylum seekers were unable to submit applications during this time, a senior prefecture official told Human Rights Watch.[166]

Even after the collective ended the blockade in May 2025, the accumulation of pending applications continued to cause disruption. We heard, for example, that people in vocational training programs could not renew their training contracts because the prefecture had not yet processed their temporary residence permits.[167]

We asked an official why the prefecture tolerated the forced closure of immigration offices and the harassment of people who try to use its services. Pointing out that nearly all of the protesters are women and that many are older women, he told us, “You cannot carry out law enforcement in the same way with women as you might do with younger people. If force is used to move them, it could spark unrest in the department. . . . So the government’s position is to choose the lesser evil.”[168]

A journalist who has reported extensively on Mayotte explained, “The blockades are easy to stop since they involve only a few people. But we don’t know what the backlash would be. Their symbolic weight is significant.”[169] A staff member of an association providing administrative support to migrants, which had to close its offices after being threatened by anti-migrant groups, told us:

In Mayotte, we faced threats and intimidation from these collectives, with a total lack of support from the authorities. Today, since our office has closed, other associations are being targeted by collectives. They also target public services (the Departmental Council, the Prefecture, the hospital, etc.). It is not always visible, but services are shut down. It feels as though everyone is quite content for the blockades to continue.[170]

These delays in processing regularization requests left many people in prolonged administrative limbo and pushed others into irregular and highly vulnerable situations. Because families without valid documentation often face administrative barriers to school enrollment, these delays likely had adverse consequences for children’s access to education. Blockades and processing delays also prevented some young people from continuing their studies in Mayotte or elsewhere in France, Human Rights Watch heard.[171]

The Impact of Large-Scale Eviction Operations on Education

In 2023 and 2024, French authorities carried out large-scale eviction operations in Mayotte—most notably “Operation Wuambushu” (meaning “take back” or “reclaim” in Shimaore) and, one year later, “Mayotte Place Nette” (“Clean Up Mayotte”)—demolishing informal settlements where many migrant families and children lived. The government justified these actions as measures to fight crime, public health risks, and irregular migration. The alternative housing authorities provided was often inadequate.[172] Families that included adults without documents received no alternative housing.[173]

An official from the prefecture told us: “During demolitions, roughly between one-third and half of the people were eligible for rehousing. This concerns French families and those with regular status. Families in an irregular situation were not rehoused and resettled [on their own] a bit further away.”[174]

These operations adversely affected children’s access to education: When temporary emergency housing was offered to families with legal status, it was often located far from their schools, forcing them to choose between relocation and their children’s schooling. Many instead rebuilt makeshift shelters to keep their children enrolled. Families without legal status received no resettlement or educational support. The destruction of homes was particularly traumatic for all children, with significant and unaddressed consequences for their schooling and mental health—risks that were foreseeable but not anticipated or mitigated by the authorities.[175]

Asylum-Seeking Children Out of School

Children in asylum-seeking families are often out of school for many months after they arrive in Mayotte, the consequence of a combination of factors that include inadequate capacity in official reception centers, authorities’ reluctance to provide services to the exceptionally precarious informal encampments where many asylum seekers stay, and the protracted blockade of the prefecture.

In May 2025, about 400 people, including at least 20 children, were living in an informal encampment in Tsoundzou 2, on the southern outskirts of Mamoudzou, in crowded tents or makeshift shelters, exposed to the elements and without permanent infrastructure, with limited access to water, sanitation, food, and health care. Most were from the Great Lakes region of Africa, particularly the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, and Burundi, as well as from Somalia. Many were attempting to apply for asylum or other legal status and were facing considerable delays in the application process, Human Rights Watch heard during our visits to the encampment.[176]

As of July, about 580 people were at the site, including 100 women and 44 children, humanitarian groups told Human Rights Watch.[177]

Camp residents and humanitarian workers described a climate of constant insecurity for those staying there. In particular, women and children have faced heightened risks of violence, including sexual and gender-based abuse, in the absence of adequate protection measures. Groups of local youth from outside the encampment have repeatedly harassed camp residents, throwing stones and making threats, often expressed in racist or xenophobic terms, parents told Human Rights Watch in May.[178]

An official from the prefecture told us, “Being an asylum seeker carries a physical risk of assault. For example, a few months ago 55 Somalis were released from detention; the next day, 5 of them ended up in the hospital with machete wounds.”[179]

For months, camp residents had no running water. Humanitarian agencies had installed a single tap for the entire camp by the time Human Rights Watch visited, but there were no showers or toilets, and many tents were located near areas where human waste and other refuse collect.

Within this environment, children were among the most affected. Many were not in school. “There’s fear among Mahoran residents that children from African countries will bring diseases to school,” said an aid worker. “This has been used as an argument to keep them apart. . . . The real question is when these children will stop being trapped in camps and start mixing with other children.”[180]

In September 2025, about 20 children were enrolled for a few half-days in educational activities organized by a local association, in coordination with CASNAV, as a possible pathway to enter secondary school. Municipal authorities have been more reluctant, and some have refused to enroll these children, including in the communes of Combani and Mamoudzou.[181]

Many camp residents had been unable to apply for asylum or follow up on their applications because citizen collectives physically prevented them from entering the prefecture offices for months, as described above.

“They’re just clinging to the hope of getting their papers,” an aid worker told Human Rights Watch. “That can take months, even years. You can’t ask human beings to wait like that, doing nothing. Many have skills—teachers, nurses—that could benefit Mayotte.”[182]

Authorities issued eviction notices to camp residents on September 28, giving them 23 days to relocate before the camp’s demolition. Of the 500 residents identified by the prefecture at that time, only 330 residents were offered alternative accommodation.[183] On October 22, the day the demolition began, the prefecture stated that “more than 400 people” had been provided with shelter.[184] Nonetheless, an additional 434 people, including 25 families with children, did not receive alternative accommodation and were sleeping along the highway in the open air after the encampment’s demolition.[185]

The United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination has called on France to ensure that asylum seekers and migrants in an irregular situation have access to accommodation in practice.[186]

Fear of Document Checks

The possibility of being stopped for document checks by the border police (police aux frontières, PAF) creates additional obstacles for undocumented parents seeking to register their children for school, particularly if they are repeatedly told to obtain additional paperwork. Racial and ethnic profiling by police and other abuse of stop-and-search powers, including the targeting of children, are longstanding problems throughout France, as Human Rights Watch and other groups have documented.[187] Legislation enacted in 2018 allows unrestricted identity checks by PAF and other police throughout Mayotte (and elsewhere in France, only in specifically delineated border areas),[188] increasing the risk of discriminatory and otherwise arbitrary identity checks.

“People are limiting their movements to a minimum so as not to risk encountering the PAF,” said a member of an association that works with families in Mayotte’s informal settlements.[189]

A volunteer with another association made a similar observation, saying, “Parents’ reluctance to begin administrative procedures stems from a fear of being arrested on the way or at city hall. Even when it comes to vaccinations, they are afraid to have their children vaccinated and encounter the PAF.”[190]

An aid worker said she had heard the same from members of the communities they work with.[191]

Some children also said they feared being stopped by police even though French law does not require children to have residence documents. For instance, Mahdi A., a 15-year-old boy, told us, “I would like to have papers so I don’t have to deal with the border police. They are very dangerous. We see them, and we are afraid to go to school.”[192] Abdou M., 17, gave a similar account.[193]

A teacher explained why many of his students were apprehensive about document checks:

The PAF exceeds its authority. This is standard practice. For example, young people from Mayotte are deported because they are part of a group that is caught by the PAF, without going through the CRA [administrative detention center] [and even though] in any case they cannot [by law] be deported before the age of 18. The PAF is extremely violent during arrests. I remember a kid who had stones embedded in his temple because his head had been held down on the ground with a knee [by a PAF officer].[194]

When we asked the senior official at the prefecture about these reports, he replied that the PAF was prohibited from checking immigration documents in schools, but not in other public areas: “I cannot say that there will be no checks within 500 meters of a school,” the official said. “But there will be no targeted checks at school arrival or departure times.”[195]

Lack of Opportunities to Continue to Higher Education