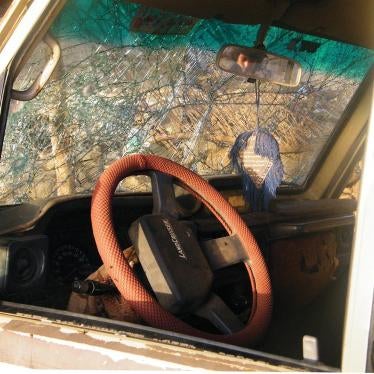

The four years since Russia’s full-scale invasion have left Ukraine littered with antipersonnel landmines that will endanger civilians for years to come. In that period, Russia’s extensive and unlawful use of landmines has caused hundreds of civilian casualties. Despite being a state party to the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty, Ukraine has also used the weapons, although the extent is unclear.

On December 1, states parties to the Mine Ban Treaty will convene in Geneva for their annual meeting. This year, they will be discussing the dangers landmines pose not only to individual lives but also to international law.

Last July, Ukraine informed the United Nations that it was suspending operation of the Mine Ban Treaty. Ukraine faces enormous security challenges posing an existential threat from Russia. The suspension, however, increases the likelihood of more civilian casualties by paving the way to greater antipersonnel landmine use. It adds to concerns already raised by the harmful, albeit lawful, withdrawal of five states from the Mine Ban Treaty—the Baltic states, Finland, and Poland—earlier in 2025. Those withdrawals are a dangerous development and could lead to the use of new antipersonnel landmines putting civilians at risk while weakening the norm against the weapons.

Ukraine’s suspension, which is unlawful as a matter of public international law, will in addition have grave international legal implications and the potential to erode the authority of international law well into the future.

States parties cannot suspend their obligations under the Mine Ban Treaty. The treaty is designed to protect civilians and thus prohibits use and other activities “under any circumstances.” It is during wartime that this and other disarmament treaties are needed most. Ukraine argues that it is allowed to suspend under article 62 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties because it experienced a “fundamental change of circumstances” since it joined the Mine Ban Treaty, but article 62 does not apply during armed conflict.

At their meeting, the other 165 states parties of the Mine Ban Treaty should oppose Ukraine’s move. They should individually voice their opposition and agree collectively to language stating that the Mine Ban Treaty does not permit suspensions. Several states—Austria, Belgium, Norway, and Switzerland—have already sent objections to the recent suspension to the UN’s Office of Legal Affairs, and France has submitted a related communication. Switzerland, for example, has said that “withdrawals or suspensions by states parties engaged in an armed conflict violate international law and undermine work on arms control and disarmament.”

States should also publicly oppose the unlawful suspension because of the broader implications for international law. There are at least six reasons why they should not remain silent.

First, other states may unlawfully suspend their obligations under multilateral treaties, including in the areas of international humanitarian and human rights law. In so doing, they would undermine legally binding instruments as a key source of international law.

Second, ignoring Ukraine’s suspension sets a precedent for looking the other way when states unlawfully avoid obligations at the time they are most essential. For disarmament and international humanitarian law treaties, that would mean allowing a state party to set aside provisions designed to protect civilians from armed conflict in the middle of an armed conflict. Under human rights law, it could involve allowing a fundamental, non-derogable right—a right that can never be waived—to be violated during a public emergency.

Third, suspensions undermine the stigma created by treaties prohibiting certain weapons or certain actions. Stigma is an important tool for influencing the actions of states and other actors outside of a treaty.

Fourth, the move risks deterring states from engaging in the time- and resource-consuming process of negotiating multilateral agreements. International law relies on good faith, trust, and predictable expectations, not just on—often weak—enforcement mechanisms. States make reciprocal commitments that limit their own options because they benefit from other states doing the same. If a state fears that others may suddenly suspend their commitments, it may conclude it is too politically, financially, or strategically risky to invest in making a commitment in the first place.

Fifth, states that think they are harmed by another state’s suspension of treaty obligations may reciprocate by suspending their own obligations toward that state.

Sixth, improper invocation of suspension mechanisms under the Vienna Convention, the basis for Ukraine’s fundamental change of circumstances argument, can blur the line between what is lawful and not. It could encourage states to use the cover of technical legal arguments to avoid respecting their obligations.

Mine Ban Treaty states parties should unequivocally condemn Russia’s widespread use of antipersonnel landmines in violation of international humanitarian law and denounce the recent withdrawals of EU member states that damage disarmament norms.

While recognizing Ukraine’s significant security challenges, states should also challenge Ukraine’s decision, which will erode the legitimacy and power of international law. Treaties should be viewed as effective and reliable frameworks for conduct. If states go unopposed in choosing when and where they respect the law, trust in the system—and in its ability to constrain abuses—will collapse.

At the Mine Ban Treaty Meeting of States Parties, 165 states parties have the opportunity to publicly and unequivocally oppose Ukraine’s suspension and adopt a clear statement that the Mine Ban Treaty does not permit suspensions by any state party. But it is not just an opportunity. For those committed to protecting international law, it should be an imperative.