Gilberto Tomazoni, global CEO of meat multinational JBS, recently advocated support for rural producers, as a way to scale up climate solutions for agriculture at the upcoming climate summit COP30. “Livestock raising can also be part of the solution,” he wrote. As such, JBS should ensure that it removes from its entire supply chain the illegal cattle ranches that destroy the Brazilian Amazon and hurt rural producers who operate lawfully.

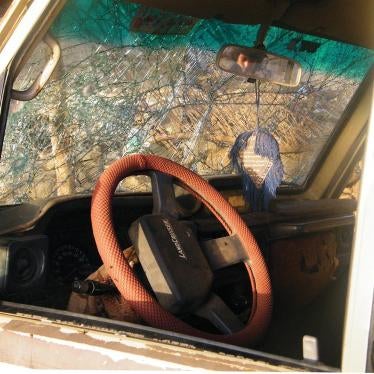

“The land grabbers made me lose 17 years of work in a matter of minutes,” a small holder told me as we walked through her burned orchard in the Terra Nossa rural settlement, in Pará state. Land grabbers encroached on the settlement, logging, setting fires, planting grass, and establishing illegal cattle ranches. After repeatedly denouncing the crimes, she became a target for threats and narrowly survived an assassination attempt.

Our Human Rights Watch report “Tainted” highlighted several cases of rural producers in Terra Nossa whose livelihoods were devastated by illegal ranches. Most of the settlement was covered in primary rainforest, but ranchers converted nearly 40 percent to cattle pasture. We obtained permits issued by Pará’s animal health agency showing that JBS’ direct suppliers procured cattle from these illegal ranches.

Terra Nossa shows the struggle between lawful rural producers and environmental criminals in the Amazon. In our report, we clearly distinguished between these groups. But JBS slaughterhouses cannot make this distinction because they generally can’t identify their indirect suppliers.

Cattle passes through multiple ranches before being sold to slaughterhouses. JBS slaughterhouses monitor the ranches they buy cattle from, but don’t know where those ranches got the animals. This approach obscures the origin of cattle illegally raised on protected areas.

In response to our report, JBS defended their procurement practices, saying they follow the Beef on Track protocol. This is positive, but the protocol does not track indirect suppliers. This issue isn’t new. JBS originally pledged to track indirect suppliers by 2011, but 14 years later they still don’t. Their most recent deadline is January 2026. Will they deliver?

The Brazilian Beef Exporters Associations (ABIEC) also reacted, saying we did not consider the important policies that Brazil has enacted in recent years.

In fact, we described at length the state of Pará’s recent policies to trace cattle and we interviewed several officials in charge of implementing them. But as one of the cases we detailed shows, illegal farms in Pará can sell to intermediaries in Mato Grosso, and the latter supply a JBS slaughterhouse in São Paulo. Without a federal solution, tightening regulations in Pará simply moves the problem to another state.

This is why we also praise the federal government’s announcement of a traceability system for the whole country. This is standard for many countries. But that system is not due to be fully operational until 2032. This is so long into Brazil’s future, it comes across more as a vague aspiration than a real goal.

Brazil has strong environmental institutions that monitor the rainforest and they recently delivered the good news that deforestation in the Amazon as a whole has dropped. Entrenching this downward trend requires an institutional response to address the country’s largest driver of deforestation: cattle ranching. Establishing a federal cattle traceability system is certainly a key step in this direction, but intentions have to translate into practice.

Illegal ranches have thrived in Terra Nossa because there was always someone to buy from them. Meanwhile, lawful rural producers suffer violence and dispossession. “All I want is what is mine and that the justice system upholds the law,” the rural producer from Terra Nossa told me. Is she not right?